A house is not only a space on the ground. It is a physical identity of the owner. Losing a house means losing half of the soul.

This is a reality which has been faced by the people of Surabaya since 1900. Industrialization, polarization, and war stripped civilians of their houses and forced them into the slum areas of Surabaya. This city of heroes was formerly known as the city of refugees; then a space acquisition occurred to claim back the civilians’ identity.

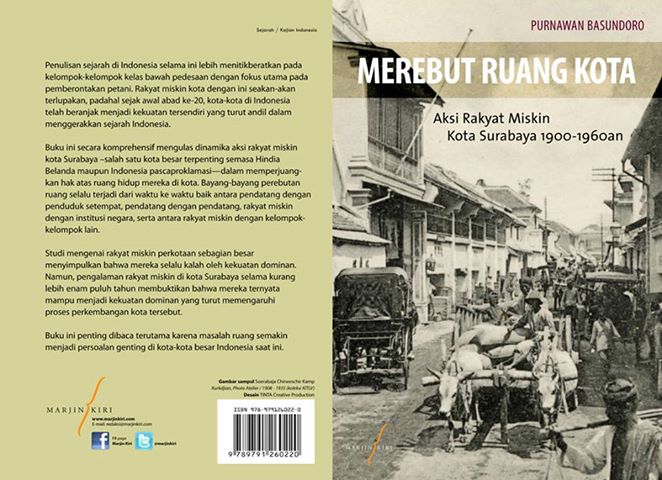

“Merebut Ruang Kota”, a book based on the dissertation written by Purnawan Basundoro, takes the reader back to how the poor acquired the city’s spaces from 1900 to 1960. The poor were defined as those not having access to the city’s spaces. In the book published by Marjin Kiri, the poor are split into two groups.

The first group is the rural people who urbanized due to industrialization. The unemployed people expected to have a better life in Surabaya. However, instead of having a wealthy life due of space acquisition, they could find neither jobs nor houses to live and ironically had to live on the streets. Indeed, Surabaya was devastated by its over-urbanized population.

War was responsible for the growth of the second group of the poor. During the revolution, Surabaya, which had been a place for battle (especially from 1945-47), forced its civilians to flee outside the city for at least two years. Unfortunately, when they finally came back to Surabaya, they found that strangers had taken their belongings. They could not even claim back their land as the legal certificates were often lost during their evacuation. Hence, they were alienated from their own land.

In their effort to live, poor people then claimed any spaces they found, starting with the houses left by the war refugees. When thousands fled from Surabaya, thousands more arrived to fill these abandoned spaces. When there were no more private spaces left, public spaces were in turn acquired.

Partikelir land (rented land owned by a landlord) was the first public area acquired by the poor. An example of this is the Baswedan’s land which extended from Airlangga University until Pucang and Karang Menjangan area. Thousands of immigrants made blocks of houses, changing the public area into a private area. Likewise, there was an acquisition of cemeteries, especially those owned by the Chinese. “During the process of fixing land, there were many corpses on the street,” said Purnawan. As the cemetery is changed into living spaces, the former owner families were even restricted from burying their relatives there.

The historical story of space acquisition in Surabaya is completely discussed in Purnawan’s book. His research is so lively and full of important dates which occurred during the development of the city. It was written with a spatial perspective of Surabaya and completed with the stories of civilians during times of acquisition. For example, there is the story of Tante Dolly, who formed the prostitution sector and manipulated the Communist issue in order to clear the street of homeless people.

History has proven that space acquisition will always occur. According to Purnawan, the most interesting part is the way in which the poor showed their ability to survive by creating their own spaces. There was more evidence about how the poor could construct their own lands without top-down intervention from the government. They just legalized what the civilians had created on their own.

“This book affirmed that the city does not belong to elites only,” said Purnawan in a book discussion at C2O, last Monday, “the city acquisition will be stopped only when there is equilibrium.”

However, the history lecturer at Airlangga University was sure that equilibrium is never meant to happen and there will always be a dynamic process in an attempt to reach it. That being said, urban problems such as land availability, traffic, and pollution are the problems of both the poor and the rich. The next policy causing concern for both the government and the people is how to construct the canals to evenly distribute resources among spaces.

Links:

- YouTube record of the discussion

- Twitter timeline (in Indonesian)

- Buy this book (and other Marjin Kiri books) in C2O

English translation edited by Joseph Taylor.

This post is also available in: Indonesian