More than a decade after the fall of Soeharto in 1998, with the waning of political discriminatory policy and cultural bias against Chinese Indonesians, a number of films dealing with the issue of Chinese Indonesian culture and experience have been publicly released. To name a few, we have Ca Bau Kan (Nia Dinata, 2002), Babi Buta yang Ingin Terbang (Blind Pig Who Wants to Fly, Edwin, 2008), The Anniversaries (Ariani Darmawan, 2006), Anak Naga Beranak Naga (Dragons Begets Dragons, Ariani Darmawan, 2006), A Trip to the Wound (Edwin, 2007), Sugiharti Halim (Ariani Darmawan, 2008), and Cin(T)a (Sammaria Simanjutak, 2009). These films tell the continuous (re)negotiation of “Chineseness”, the dynamics of Chinese discrimination and assimilation, usually through the narrations of their ideas, experiences, emotions, and ambiguities of being Chinese in Indonesia. Due to the difficulties in screening them through mainstream cinema, most of them are screened in festivals and local communities.

Rumah Abu Han Documentary Film from kevinranting on Vimeo.

Rumah Abu Han (The Han’s Ancestral House) documentary, then, is noteworthy for (re)telling the stories of Chinese assimilation and integration within its surrounding environment and communities by focusing on a physical, tangible heritage, and for its method of distribution through a social video-sharing website, Vimeo. This short, 22-minute documentary was released this year, directed by Kevin Reinaldo Arffandy, a recent graduate from Petra Christian University, Surabaya, for his final year assignment, and produced under his independent production house, Ranting Pohon production.

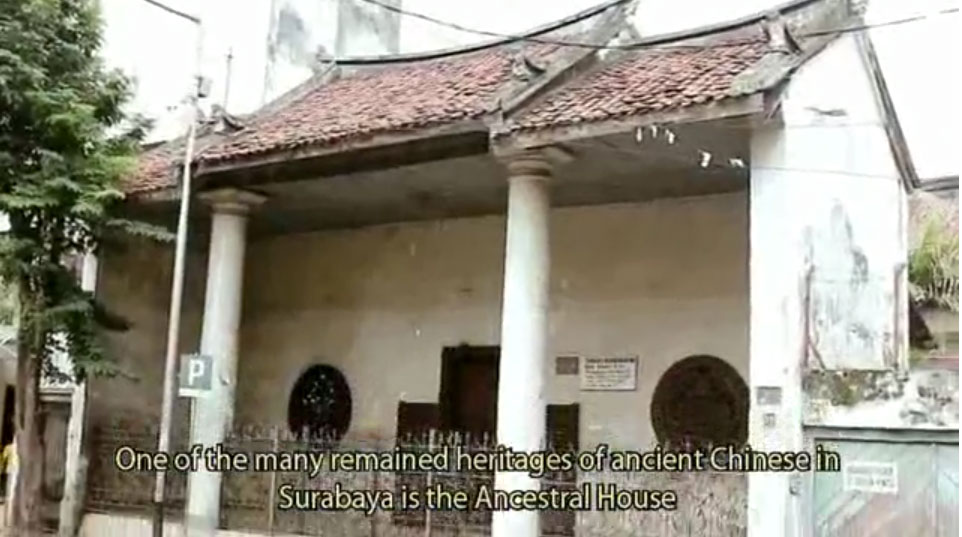

In Surabaya, Indonesia, there are three well-known Chinese ancestral houses, owned by the clans of Han, The and Tjoa (Onghokham, 2005). The Han’s ancestral house is perhaps the best known since it is the biggest, the oldest, still well-maintained and is relatively accessible to the public. This documentary attempts to show the integration of Chinese, Dutch and Javanese cultures by tracing the architecture and the interior elements through narrated descriptions and interviews with the owner (Robert Rosihan), the caretaker (Karno), a local heritage community (Freddy Istanto) and a lecturer from Petra Christian University specialising in Chinese heritage (Hanny Kwartanti).

The film opens with a general overview of Surabaya as a bustling, modernising city with common urban problems, and here the filmmaker laments how the rapid urban growth has led to the indifference and disregard for their own cultural heritage and history. Through an interview with Freddy Istanto, a well-known media campaigner from the Surabaya Heritage Society, the film attempts to promote the importance of preserving cultural heritage in establishing the city’s sense of place and identity—the ‘spirit’ of the city.

Before focusing on the ancestral house, the film briefly explains how the old town area of Surabaya near the Kalimas river and Jembatan Merah bridge was divided by the Dutch colonial government into three areas based on the ethnicities—the Maleische Camp for the Malays, the Chineezen Camp for the Chinese, and Arab Camp for the Arabs. This division has contributed in shaping the routines of everyday life, the patterns of settlement, and the physical environment.

The film then begins to focus on the house, highlighting the interior elements and the history of the Han’s family through interviews with the owner, Robert Rosihan. Located on Jalan Karet, the Han’s ancestral house was the first ancestral house in in Surabaya, built circa 18th century by Han Bwee Koo, the 6th generation of the Han family first arriving in the coastal city Lasem in 1673. Although rumah abu literally means a house of ashes, it is not a mausoleum (which in Surabaya is also confusingly called in the exact same term, rumah abu). The family’s preservation of its ‘authentic’ use and elements is also highly commended despite the lack of governmental and other external support.

Han Bwee Koo, the 6th generation of the Han family first arriving in the coastal city Lasem in 1673

The main feature of the house highlighted in this film is its iconic blend of Chinese, Dutch colonial and Javanese architectural and interior elements, reflecting the history, the socio-cultural values, and the tropical location. It is a well-championed—if perhaps slightly romanticised—interpretation of the Han’s ancestral house, also proposed by Hedy C. Indrani and Maria Ernawati Prasodjo (2005) in Tipologi, Organisasi Ruang, dan Elemen Interior Rumah Abu Han di Surabaya, an article Arffandy most likely referred to in making this documentary.

3D rendering of Rumah Abu Han

There are two main areas in the house: the prayer area and the living area. The prayer area is divided into the terrace, the guest hall, the family hall, and the prayer hall, while the living area contains bedrooms, bathrooms and the kitchen. To describe this interior of the house, the film uses 3D floor plan renderings and lingering shots of the interior elements like wooden carvings, floor tiles and window patterns. Hanny Kwartanti is interviewed to elaborate on symbolic interpretations of the Chinese interior elements. The film then scans and briefly describes the rooms, the origins of some architectural elements (pillars imported from Glasgow, decorative carvings from China), the furniture (Dutch-style chairs, Chinese marble tables), as well as the Han’s family portraits and their genealogy chart. A particular attention is given to the prayer hall, which is indeed originally designed as the most important area of the house. This is where the ancestral tablets (called “sinci”) are stored, and where the family burns incense at the altar and prays to their ancestors.

Ancestral Tablet (sinci)

The film then moves to describe the current use of the house through interviews with the owner and the one of the caretakers, Karno. The owner elaborates that the house has been opened for public on numerous occasions for educational purposes, including research, school trip, book discussion, and batik encim exhibitions. What is sadly missing to be documented in this film, however, is the description of the surrounding environment, which have contributed greatly in making regular public functions and opening hours thus far impossible.

Fortunately, we had the privilige of organizing a public screening and lecture at C2O Library, supported by a Surabaya historic community called Surabaya Tempo Dulu, and the Centre for Chinese Indonesian Studies from Petra Christian University. The panelists were Arffandy himself, Robert Rosihan, and Lukito Kartono, a lecturer specialising in Chinese and Indonesian architecture.

This public event has prompted questions, dialogues and ideas. Compared to other ancestral houses in Surabaya, the Han’s as a privately-owned heritage building is the most publicly accessible and relatively well-maintained, but it is still admittedly in dismal condition on a brink of disuse. The standard idea to turn it into a museum, a café, or other public space is inapplicable due to the surrounding heavy loading and unloading zone, and the questionable safetiness of the area. The owner has also revealed that the ill-defined category of ‘heritage building’ in Surabaya has on the contrary made the maintenance problematic, particularly with its heavy land taxes and complicated renovation procedures. Kartono has also supplemented the information from the film with a complex historical and architectural analysis.

With his focus on the interior elements, Arffandy can only give us an exterior overview of the Han’s ancestral house. Graduated with a degree in Visual Communication and Design, Arffandy has directed and produced a visually appealing documentary with a particular focus on visual elements and forms of the house. Unfortunately, though understandably, there is a lack of historical and environmental contexts. The emphasis is placed on obvious symbols such as dragons, lions, ancestral tablets, and the readings of visual elements from the interviews are rather restricted to Chinese symbols, with link them to various influences. Granted, this lack of exhaustive information perhaps can also be attributed to the paucity of accessible and credible historical information about Surabaya. Indeed, aside from the films by Ariani Darmawan, most films dealing with the issue of ‘Chineseness’ mentioned above usually remain within ambiguous questions of identities, ideas and experiences. This is where a venue for public screening and forum is necessary for the filmmakers to garner feedbacks for their works.

Overall, Rumah Abu Han Documentary with its attractive visuals and photography serves as a appealing audio-visual introduction, much-needed to promote a relatively obscure heritage building of Surabaya. Even in Surabaya, not too many people know the existence of this house, a fate that has befallen many other numerous old buildings of this city. Hopefully, the creation of this documentary by a young Indonesian filmmaker, with its utilisation of a global, far-reaching video-sharing website, will prompt greater interests in the ancestral house, and other oft-neglected heritage of Surabaya.

This review was first published in the Newsletter 59 Spring 2012, International Institute for Asian Studies, p. 37.

This post is also available in: Indonesian